The Hinksmans in Suffolk

Written by Ian Davis. Started 23rd August, 2023. This is a work in progress. The substance of the story is complete but there are still some rough edges and missing areas that need to be fleshed out. Last update was 3rd July, 2024.

For many years the origins of the Hinksman name in our family was a mystery. We had discovered early on in our research that Richard Hinksman had been born in Beccles in Suffolk in the early 1830s, but we could find no trace of any other relations in the area. Eventually we uncovered workhouse records that led us to Richard’s mother, Jane Hinksman, my four-times great grandmother and a woman whose life was both short and difficult living on the margins of poverty.

Even armed with this information we still faced a major brick wall finding her parents. There were tantalising traces spread through the records in the area: the marriage of an Edward Hinksman, the death of a Maria Hinksman in the workhouse, a Jane Hinksman baptised in Essex. None of these really fit together until we discovered that Jane had married in 1840 to a man named William Rouse. She stated her father’s name as William, a soldier.

This was enough to finally uncover the full story:

Jane was born in Colchester, Essex in 1809, the daughter of William Hinksman, a soldier from Hampshire temporarily stationed there, and his wife Jane Fisher, who may have originated from a village on the border of Suffolk and Norfolk. William served throughout the period of the Napoleonic wars including two deployments to Portugal, although on the latter of the two he was struck with fever for over a year. William died in 1820, on deployment to the the island of Tobago in the West Indies, while his wife, Jane, may have died earlier in 1812.

Some time before 1826, either orphaned or abandoned by her parents, Jane Hinksman entered the workhouse for the first time and in the following years gave birth to two illegitimate children: Richard and Maria. As an adult, she lived close to poverty near Beccles, Suffolk, raising her two children, before dying at the age of 32 in 1840, orphaning both and consigning them to spend the rest of their childhood in the workhouse.

At the age of 14 her son, Richard, left the workhouse when he was apprenticed into the Merchant Navy. He departed Suffolk and worked the ships that sailed the coast of England, meeting his Yorkshire-born wife, Mary, before finally settling in Newcastle-upon-Tyne to raise their family, including my ancestor Elizabeth Hinksman.

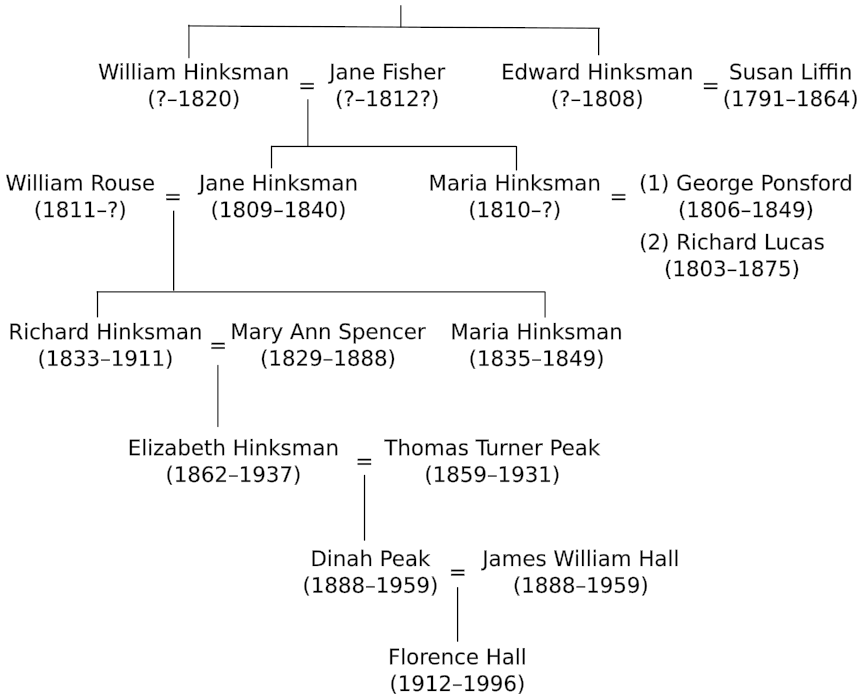

Family Tree of the Suffolk Hinksmans

William Hinksman’s early military service

Jane’s father, William Hinksman, was recruited into the 1st Battalion of the 4th Regiment of Foot on 28th July, 1799. From its founding in 1680 the regiment, known as the King’s Own Regiment, had an illustrious history, playing a major role in the American War of Independence in 1776 and, after several years service in Canada and Newfoundland, had returned to England in 1798.

At the time of William’s recruitment the regiment were stationed at Horsham Barracks in Sussex. William was recruited into the 1st Battalion as a private. There is, unfortunately, no record of his recruitment, however a note is written against his entry in the July 1799 muster rolls: “Sth Hants”1.

Just 17 days after joining the army William was promoted to the rank of Corporal in Captain Hitchman’s company1. A note in the muster rolls reads “from Sth Hants”. A couple of weeks later he was recorded as a sergeant in Captain Lamonte’s company1 and the next month moved to Captain Healey’s company, still with the rank of sergeant, where he remained until the end of 1799.

Sergeant in uniform c.1807, armed with spontoon

Typically a private might reach corporal rank within a year or two and take several years to reach the rank of sergeant. It was normally necessary to have solid military experience and a good level of educational achievement. William’s rapid rise might suggest that he had prior military experience. The month of his recruitment also saw the recruitment of several hundred men into the regiment from the militia forming new 2nd and 3rd battalions so it is possible that he transferred from the South Hampshire Light Infantry militia and the two references to “Sth Hants” are referring to that transfer. 2

In September of 1799 the regiment was ordered to Holland to join the Anglo-Russian invasion of the Netherlands. They fought at Bergen on the 19th and advanced to Castricum on the 6th October where they were defeated by the combined Dutch and French Republic forces. The regiment suffered heavy losses and retreated to England, landing at Yarmouth and proceeding to Ipswich where they spent the winter3.

The following summer William transferred to Captain Murray’s company and, on the 3rd June, was demoted from sergeant to private4. There is no indication of the reason for this demotion. Quite probably the cause was some misconduct such as drunkenness or theft. He remained a private in Captain Murray’s company until the end of 1801 when he was recorded as being part of Captain Wilson’s company. He was noted as being at “Tolbury”5 while the regiment was at Horsham, having spent most of the year at Winchester. Tolbury is possibly a variation of Tilbury, a coastal town in Essex.

In January 1802 William re-attested in Captain Chaplin’s company and was promoted back to the rank of Corporal in June6. The situation in Europe and the United Kingdom’s involvement had changed following the signing of the Treaty of Amiens. The men of the 4th having been engaged to serve during the war were offered a bounty to enlist for unlimited service. Over nine hundred did so and were constituted as the first battalion3. The remaining 2nd and 3rd battalions were disbanded later that year.

The peace in Europe was short lived and in May 1803 Napoleon, then the first consul of the Republic, declared his intention to invade the United Kingdom. As part of the preparations for invasion the 4th Foot were relocated to Shorncliffe with three other regiments as well as five companies of rifle corps. Shorncliffe was a major military camp near Cheriton in Kent, situated on the English Channel opposite Boulogne and Calais on the French side.

Jane Fisher

On 30th September, 1803 William married Jane Fisher at Cheriton in Kent, just half a mile from Shorncliffe. He was recorded as a bachelor, she a spinster. The witnesses were Isaac Munger and Mary Munger. Sadly their ages or occupations are not given (other marriages for later years in the marriage index include that information). It appears that Isaac Munger was a private from the same regiment, originally from Basingstoke in Hampshire, who enlisted at the same time as William. He was discharged in 1815 having been shot in the back at St. Sebastian.

The banns for their marriage were also read in Winchester, St. Maurice on the 10th, 17th and 24th of July7. At that time William was noted to be recruiting in Southampton in the muster rolls. Prior to becoming Hampshire, the country was officially titled the County of Southampton. The use of Southamptonshire was an informal term for the county, so the presence of the phrase “Recruiting in Southampton” may indicate William was recruiting in a number of places around the county.

The resumption of hostilities with France and the prospect of overseas deployment of the regiment may have prompted the marriage between William and Jane. As a soldier’s wife she could expect better treatment in his absence and would have been entitled to half a soldier’s ration and his pay would be available for upkeep. In the event of his death she may also have been entitled to any payment or pension due.

I have a number of theories for Jane Fisher’s origins:

First, she could have been native to Cheriton. The existence of earlier banns to marry in Winchester discounts this theory heavily. There are no other appearances of the names Hinksman in the baptism, marriage or burial indexes for Kent. The name Fisher does not appear in the Cheriton registers until the 1880s so it seems that Jane Fisher was not local. There is only one other contemporary mention of a Fisher, a baptism of Anabella Fisher twelve years later in 1814. She was the daughter of another soldier John Fisher. This is probably just a coincidence and not a relative of Jane.

A second possibility is that she was a camp follower. Contrary to modern connotations camp followers referred to all persons, male or female, who were allowed to follow the army on campaign. They were subject to the same martial law as soldiers and were considered to be part of the army. They included surgeons, commissaries, muleteers, carters, farriers, victualers and private servants of officers. Unmarried women also followed the army but were generally under the protection of one man and considered a mistress rather than a prostitute. 8

Another possibility is that Jane was the daughter of another soldier present at the camp in Shorncliffe, either in the 4th Foot or one of the other regiments. That soldier could well have originated from Suffolk but he would presumably have enlisted 15-20 years before William. In those years the regiment was most active in America, the West Indies and Canada.

One intriguing link hints at a connection with Suffolk or Norfolk though. When her daughter Jane married William Rouse in 1839 the witnesses were William and Margaret Fisher. The marriage took place in Earsham near Beccles on the Norfolk/Suffolk border. It is possible that William and Margaret were relatives of Jane Fisher, perhaps her brother and his wife. A William and Margaret Fisher appear in the 1841 census for Earsham aged 49 and 51, both born in Norfolk9. William Fisher would have been 11 at the time of Jane Fisher’s marriage, so its possible he could have been a younger brother.

If Jane was from Suffolk or Norfolk then what opportunities did she have to meet William Hinksman? Although the 4th Foot passed through Suffolk after their return from Holland in 1799, marching from Yarmouth to Ipswich, it is unlikely they would have passed by Earsham. It seems a stretch to imagine her meeting William en route to Ipswich and following the army for four years until their marriage.

A final theory is that Jane was from Hampshire. If, as seems likely, William was also from Hampshire then Jane may have been someone he knew when growing up or was a relative of another local family. Alternatively William may have met her while recruiting in 1803, possibly in Winchester where their banns were first read.

Edward Hinksman

Edward Hinksman was one of the new recruits made in Southampton. He was recruited on 28th July, 1803 by Ensign Craig, almost certainly the leader of the recruitment group William was part of10. Edward got £3 17s 6d, Craig got 5s.

Ensign Craig continued to recruit through August but William stopped recruiting on the day Edward joined. This, as well as sharing a name, is suggestive that they knew one another and were possibly brothers.

This is further reinforced by the fact that William and Jane were later to be the witnesses to Edward’s marriage to Susan Liffin in 1806. At various times between 1806 and 1807 they appear to be on furlough at the same time as one another.

The November following William’s marriage to Jane Fisher the regiment proceeded to newly built barracks at Hythe before returning to Shorncliffe in 1804. The threat of invasion from France passed and at the end of the season, on 2nd November the regiment returned to Hythe. They left for Canterbury on 9th March 1805 and then spent the summer encamped on Beachy Head.

On the 21st October, 1805, the British won the battle of Trafalgar and on the 27th the 1st battalion embarked at Ramsgate for Hanover, from which the French had withdrawn. William at that time was in the 1st battalion and was likely part of that deployment although I haven’t had access to the muster rolls of that period to confirm his whereabouts

The regiment were not involved in action and, after a major defeat of the allies by the French at Austerlitz, withdrew to England. They landed at Yarmouth in February 1806 and proceeded to Woodbridge in Suffolk, about seven miles northeast of Ipswich.

This is where, on 7 March, 1806, Edward Hinksman married Susan Liffin (or Liffen). He is noted as being of the 4th Regiment of Foot, she is recorded as being of the parish of Woodbridge. The witnesses were William and Jane Hinksman. Jane couldn’t write her name.

Susan was most likely born about 1791 in Barsham, Suffolk, 25 miles north of Woodbridge and just a mile west of Beccles. She would have been 15 or 16 when she married Edward.

After Edward’s death she remarried to William Beck in Weston, Suffolk, two miles south of Beccles. In the 1841 census they are living in Weston with Robert Laffin, age 80, presumably Susan’s father. They also have a child, Samuel Beck, aged 8. They appear again in the 1851 census where they both are recorded as having been born in Barsham. She died in poverty in the Shipmeadow Workhouse in 1864, aged 73. Her son, Samuel, joined the Royal Artillery and is recorded in the 1851 census in the Royal Artillery Barracks at Woolwich age 19.

In May the 1st battalion marched to Colchester. In 1807 the 1st battalion embarked for Copenhagen and, after taking the city, returned to Colchester in November. Early in 1808 the 1st battalion embarked for Gothenburg in Sweden but returned after only a few weeks of fruitless manoeuvres. They were immediately ordered to Portugal in response to the seizing of the Spanish crown by Napoleon.

The regiment landed at Maceira Bay in August and marched through Portugal to Spain, arriving at Salamanca on the 14th November. Here they faced stiff opposition from superior French numbers forcing the regiment to retreat, enduring “great privation and suffering” over 250 miles to the coast3.

In his book, The Recollections of Rifleman Harris, Benjamin Harris describes in detail the journey and the toll it took on the men and women who followed them:

The shoes and boots of our party were now mostly either destroyed or useless to us, from foul roads and long miles, and many of the men were entirely barefooted, with knapsacks and accoutrements altogether in a dilapidated state. The officers were also for the most part, in as miserable a plight. They were pallid, way-worn, their feet bleeding, and their faces overgrown with beards of many days’ growth. What a contrast did our corps display, even at this period of the retreat, to my remembrance of them on the morning their dashing appearance captivated my fancy in Ireland! Many of the poor fellows, now near sinking with fatigue, reeled as if in a state of drunkenness, and altogether I thought we looked the ghosts of our former selves11

On the 16 Nov 1808, Edward Hinksman died, possibly at Salamanca. No mention is made of the cause of death but he was at that time a Corporal in Captain Piper’s company. The regimental pay lists record that his widow received 12/10d12. William was a sergeant in the same company.

The regiment arrived at Corunna and made preparations to embark for England. On the 16th January 1809 the French attacked the British forces during embarkation. The British held off until nightfall whereupon they completed their embarkation, sailing for home. They docked at Portsmouth on 31st January and marched to Colchester to meet up with the 2nd battalion which had returned from Jersey.

Following the regiment?

It’s possible that both Jane and Susan accompanied their husbands to Portugal. Between four and six wives for every company of soldiers were traditionally allowed to sail with British troops bound overseas. Sixty per battalion is given as a typical number for the Peninsular War. Women allowed to go abroad with a regiment were chosen by lottery. The nature of the lottery varied from one regiment to another, but there was always some kind of preselection. The choice fell, as a rule, upon useful women without children, such as nurses or laundresses. The lottery was deferred until the evening before the regiment was due to sail.8

Both might have been eager to follow the regiment, despite the prospect of hardship on the way. The fate of women left behind was uncertain. They were left in an unfortunate economic position, for the regular army paid no family allowances at all and took no formal responsibility for dependants of soldiers sent abroad. In an economic sense, widowhood might have been preferable to being left. A widow can remarry, and the government did provide small pensions for the widows of dead soldiers. The wife left behind had no such recourse. She could find work to support herself and her children, or she could seek poor relief.8

Women travelling with an army were expected to keep up with the line of march, generally fifteen to twenty miles a day in good weather, while bearing any children or family possessions. Army regulations forbade them to ride in the baggage carts, so many acquired donkeys. The donkeys allowed them to ride instead of marching and to range farther into the countryside in search of food to supplement the ration.

We have a record of a hand-written schedule showing “Return of the Women and Children of the 1st Battalion of the 4th Regiment of Foot who received the allowance to take them home on the Battn’s being ordered to Portugal.” Among those in receipt of 1/1/- was Mary Hinksman, of Piper’s Company. However we did not record the date of the schedule, but it is from either 1808 or 180912. This note is suggestive that at least one woman married to a Hinksman did not travel to Portugal, but instead was assisted to travel home. However, it’s not clear who Mary is.

There is also a John Hinksman mentioned, who enlisted in the 4th Foot regiment on 19th April 1804. I haven’t followed up all his references in the records but it is possible that Mary is his wife.

Not every overseas deployment resulted in the wives being sent home. When some portion of the regiment remained at home barracks the women and children were likely to remain too. In the muster roll for Jun-Sep 1807 there is a schedule of allowances paid to the women of the regiment to take them home when the regiment was deployed to Copenhagen. Neither Jane or Susan are mentioned among the women. It’s not clear whether they travelled with their husbands or remained at barracks, all we know is that they did not receive an allowance to travel home.

Jane and one child received received £1-6 to return home on the deployment of the regiment to the Netherlands in July 1809 and £1-11 for her and two children in October 1810 when the regiment were sent to Portugal once again13.

Fever

On 16 July, 1809, William’s regiment formed part of an expeditionary force to the Netherlands intended to destroy the French fleet and fortifications around Antwerp and the island of Walcheren.

The regiment departed from Deal and landed on the 1st of August on the island of South Beveland, where it was stationed during the attack and capture of Flushing. William was one of an estimated 8,000 soldiers incapacitated by “Walcheren Fever”, most likely a combination of malaria, typhus, typhoid and dysentery. He spent 16 days in the general hospital. In September the regiment was withdrawn from South Beveland and returned to Colchester Barracks with much reduced numbers.

Benjamin Harris described the scale of the disease:

The company I belonged to was quartered in a barn, and I quickly perceived that hardly a man there had stomach for the bread that was served out to him, or even to taste his grog, although each man had an allowance of half-a-pint of gin per day. In fact I should say that, about three weeks from the day we landed, I and two others were the only individuals who could stand upon our legs. They lay groaning in rows in the barn, amongst the heaps of lumpy black bread they were unable to eat.11

He goes on to describe his own experience of the fever:

At that moment I felt struck with a deadly faintness, shaking all over like an aspen, and my teeth chattering in my head so that I could hardly hold my rifle.11

And the scene when the sick men landed in England:

The Warwickshire Militia were at this time quartered at Dover. They came to assist in disembarking us, and were obliged to lift many of us out of the boats like sacks of flour. If any of those militia-men remain alive, they will not easily forget that piece of duty; for I never beheld men more moved than they were at our helpless state. Many died at Dover and numbers in Deal.11

In March 1810 William and Jane had another daughter, Maria, also in Colchester.

In October of that year William was sent to Portugal with the 1st battalion. Jane and her two daughters received an allowance of £1-11s to take them home. William unfortunately became sick on arrival in Lisbon. He was absent from all musters from November 1810 through to February 1812 and spent a total of 162 days in the general hospital.

This sickness may have been a recurrence or continuation of the fever William had caught in Walcheren. Benjamin Harris describes how after Walcheren he spent four years recovering in barracks, at his parents home and in various hospitals, six months of which were spent in bed unable to move11.

The Tower of Belém, Lisbon, Portugal.

William recruited for the regiment from 1813 through to March 1815, managing to enlist nine new soldiers, all from Southampton. In the meantime the 1st battalion pursued the French into France, blockading Bayonne for several weeks in the spring of 1814. Upon the abdication of Napoleon the regiment embarked for North America to reinforce the forces that were fighting the United States. They took part in the capture and burning of Washington before returning to England in May 1815, taking up station in Deal. Just a month later they embarked once more for France and fought in the Battle of Waterloo.

William was based in England throughout this period. He moved with the 2nd battalion to Deal in June 1815 where he appears to have stopped his recruitment efforts. At the end of 1815, with the conclusion of the wars against Napoleon, the 2nd battalion was disbanded. By March 1816 William was recorded as being a member of the 1st battalion, stationed at the depot in Deal. In September he was transferred to France to join the rest of the regiment at St. Omer in the north east. A few weeks later they relocated to Frankenburg then in the Kingdom of Westphalia.

The regiment’s numbers were now reduced to 45 sergeants, William included, and 800 rank and file. They remained encamped in France for a further two years. Finally, at the end of October 1818 they returned to England, departing from Calais on the 29th and arriving in Winchester two days later.

William was to remain in England for only a few months before the regiment was ordered to the West Indies. They arrived in Barbados on the 5th April and the next day six companies sailed for new headquarters at Grenada, two companies to Trinidad and a further two companies for Tobago. William was assigned to one of the latter companies at Tobago where he was to remain for another 12 months.

The two companies at Tobago suffered severely from fever and lost four officers, 84 sergeants and rank and file until they were relieved in September 1820. By that time their numbers had been reduced to one officer, four sergeants, two drummers and just 35 rank and file3.

Unfortunately the relief came too late for William. He died on 30th March 1820 in Tobago, the entry being made in the muster roll for June 182015. He left behind effects worth £15 18s 3d, far greater than any other soldier who died in that quarter. It is unknown whether any of this money was directed to his surviving family.

The fate of the soldiers families?

The fate of William’s wife, Jane Fisher, remains a mystery. There is no mention of her after October 1810 when she was recorded in the schedule of women remaining behind when their husbands embarked for Portugal. She is recorded as receiving an allowance of £1-11s to take her and her two daughters home.

If a wife did not travel with her husband she would have no automatic support from the army. She could apply to her home parish for poor relief - after she had made her way there, often a considerable distance from the embarkation port, with her children, if any. No formal allowance was given to the woman to help her on her journey, though local parishes might choose to assist her to return home, or the regiment might have raised charity funds for that purpose.

There is a record of a burial of a Jane Hinksman at Portsmouth, St. Thomas on 10 Aug 181216 but there is no other identifying information and could be unconnected.

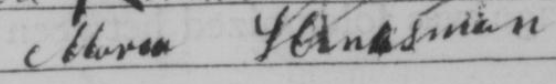

Their daughter Maria married George Ponsford in Alverstoke on the 6th January 1828. Alverstoke is a parish just across the harbour to the west of Portsea and Portsmouth.17. Together they had nine children, giving two of their sons Hinksman as a middle name: William Hinksman Ponsford, born 1831 and Harry Hinksman Ponsford born 1844. Maria was literate and must have cared about her origins, signing her name as Maria Hinksman on her marriage to George Ponsford (despite the vicar writing Hinxman).

By 1836 they had moved to Fratton in Portsea and were living at Nance’s Row which was the centre of a major cholera outbreak in 1849. George succumbed to the disease and died on the 15th July that year. In the 1851 census Maria is still at Nance’s Row and she is recorded as a shop keeper, although the type of shop is not noted.

Maria married once again, in 1860, to Richard Lucas, a gardener. On her marriage entry she states her father’s name as William Hinksman, sergeant. I’ve not managed to find the date of her death but by 1871 Richard was in the workhouse and a widower.

Edward’s widow, Susan, did return to Suffolk and married William Beck in 1811. By 1861 she living in Pudding Moor in Beccles, age 70 and once again widowed and on parish relief. Her place of birth is Barsham, Suffolk. In the next house was a Harriet Rouse, unmarried, age 45, a shoe binder born Beccles. I wonder if she is related to the Rouse that Jane Hinksman married.

My current theory is that Jane Fisher died in 1812 in Portsmouth, just after William returned from Portugal. Their daughter Maria was sent to live with family in the Portsmouth area, presumably William’s while Jane was sent to family in Beccles, Suffolk, possibly relatives of Jane Fisher if she was from there. Maybe they were the William and Margaret Fisher mentioned as witnesses on her daughter’s marriage to William Rouse? Alternatively Jane may have been taken in by Edward’s widow Susan who was living in or near to Beccles.

Both Maria and Jane were literate, signing their own names on their marriage entries, which is unusual for women of the time. Possibly their father’s wages and effects were directed towards his two daughters upbringing and education.

Jane Hinksman

Jane Hinksman, the daughter of William Hinksman and Jane Fisher and my direct ancestor, was baptised on 30 Apr, 1809 at St. Leonard’s Parish Church, Colchester in Essex. Her name was recorded in the parish register as Jane Inkman.

William had departed for Portugal in August 1808 and returned to Colchester in February of 1809 after the disastrous retreat to Corunna. Jane must have been conceived mid-1808 shortly before William departed to the Peninsular.

The first definite record of Jane after this is on 20 Mar 1824 when she entered the House of Correction in Beccles age 15, convicted of an unstated misdemeanour18. She spent four weeks in the prison, sewing linen and prisoners clothes. Her trade was recorded as an apprentice, so perhaps she already had some sewing skills.

Two years later, on the 11th October, 1826, she was admitted to the workhouse in Shipmeadow, Suffolk, just a few miles west of Beccles and Weston where her aunt Susan was living with her new husband and family. It was also a few miles east of Earsham where the Fishers were living, who may have been relatives of her mother Jane Fisher.

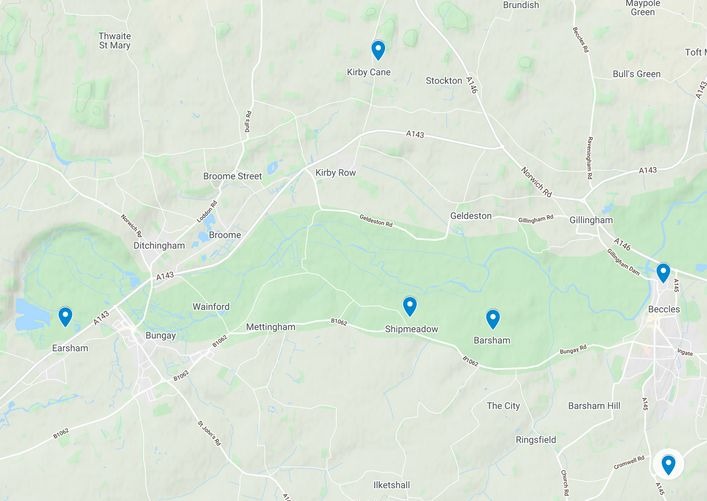

The following map shows the relationships between Beccles, Shipmeadow, Earsham, Barsham and Weston:

The master of the workhouse wrote that Jane, age 18, was admitted to the pest house for cure of venereal disease. The pest house was an isolation hospital situated a short distance to the south of the workhouse.

A month later she absconded from the workhouse. She vanishes from the records for seven years until, in 1834 she is recorded as being discharged from Shipmeadow workhouse again, now with a son, Richard, aged 2 years. Jane was 25 at this time and she is recorded as being from Beccles. Richard is another of my direct ancestors. His place and precise date of birth are still unknown but he was most likely born in 1833.

The pair were re-admitted to the workhouse on 19th November 1834 and again on 30th April 1835 staying until the 5th August. During this time, on the 12th July 1835, she gave birth to a daughter Maria, perhaps named after her sister. On their discharge they were granted an allowance of two shillings per week.

Four years later, on 8th July 1839, Jane married for the first time. She was now thirty years old. Her husband was William Rouse and they married in Earsham, six miles to the west of Beccles. Jane was recorded as living in the parish, she was a spinster and her father was William Hinksman, a soldier. There is no indication that he was deceased. William Rouse was living in Geldeston, a bachelor and was a labourer. The witnesses to the wedding were William and Margaret Fisher, neither of whom could write their names. Both William Rouse and Jane Hinksman signed their names. This may indicate that Jane received some education as part of her upbringing.

There may be a link between the Rouse family and the Fishers. In 1861 Susan Fisher, then Beck, was living in Pudding Moor, a widow aged 70 on parish relief. In the next house was a Harriet Rouse, unmarried, age 45, a shoe binder, also born in Beccles, Suffolk. Harriet would have been born around 1816 and was possibly a younger sister of William’s.

Their marriage was to be short lived. Less than a year later and a day after her daughter’s sixth birthday, Jane Hinksman died at Geldeston. The cause of death was dropsy, an abnormal accumulation of fluid most often caused by congestive heart failure, liver failure, kidney failure, or malnutrition. She was buried three days later at Geldeston.

It seems that her husband William was not able or willing to support her children. In the census of the following year both children are again resident in Shipmeadow workhouse. Sadly Maria was never to leave the workhouse again as she died eight years later of a fever.

Richard Hinksman

Jane’s son Richard, was born about 1833 in or around Beccles in Suffolk. While there’s no baptismal record for him, in July 1834 he and his mother Jane were discharged from Shipmeadow workhouse. At that time, he was documented as being 2 years old, while Jane was 25. They were listed as paupers and their place of origin was noted as Beccles.

They were re-admitted in September and again the following April. In July 1835, Richard’s sister Mary was born in the workhouse. Jane was noted as a single woman of Beccles and the next month was discharged with an allowance of two shillings per week.

Four years later, Jane married William Rouse at Earsham in Norfolk, just over the county border from Beccles. Jane was recorded as being resident in nearby Geldeston. Presumably Richard and Mary were living with her at the time. Tragically Jane died a year later in 1840 and by the time of the 1841 census both Richard and Mary were resident in the Shipmeadow workhouse again. William Rouse was not present with them, so it’s likely that he could not or would not support them after their mother’s death.

Richard’s time in the workhouse was not a happy one and he was determined to leave as soon as he could. On 25th September, 1844, aged around 11, he and a boy by the name of William Bourne left the house without permission. They returned the next day and were placed in the cells for twelve hours as punishment.

In February of 1846 a letter from Mr Leslie of North Shields in Northumberland arrived requesting boys who wished to go to sea. The board of the Workhouse recommended two boys, Richard aged 14 and William Downing aged 16, to be apprenticed. Richard was to take up his apprenticeship in August that year but in June he and a boy named John Adams absconded for three days. On their return Richard was punished more severely: he was placed in the cells for two twelve hour stints and flogged by the schoolmaster on the Saturday following his return. Both he and John Adams were restricted to bread and water. The next month he ran away again, this time with another boy, William Brown. On their return the pair were sent to Beccles House of Correction and imprisoned for a week. Their punishment may have been more severe since they stole clothing to take with them. There is no record of any further punishment but almost certainly the master of the workhouse will have required further discplining through flogging and restricted food.

Richard was bound as an apprentice to Henry James Butcher of Yarmouth on 14th September 1846 for seven years19. He was initially to serve on the Attila, a 37 ton sailing ship. However, in June 1847 he deserted the ship Mary Ann and his apprenticeship was transferred to master J. S. Adams of the Neptune in October.

Richard spent the next forty years as a mariner in the merchant navy, working on ships that plied the coal trade between Newcastle and London. In 1855 he met and married Mary Ann Spencer, the daughter of a Yorkshire cloth manufacturer. They settled in North Shields and lived for many years at Maitland’s Quay off Bell Street, right on the north bank of the Tyne where they raised their three children: Jane, Richard and Elizabeth. Elizabeth was to later marry my ancestor Thomas Turner Peak.

William’s origins

I’m fairly confident that William Hinksman was born in Hampshire. That county contains the largest numbers of Hinksman and Hinxman families and the connections to Hampshire and/or Southampton are all over William’s army records. I also think that William and Edward were brothers or at least cousins, although there is currently no documented evidence to support that.

Currently my best theory for their origin is that they were both children of Edward and Mary Hinksman of Twyford, near Winchester. Edward married Mary Bailey in 1774 and together they had eight children: Jane, William, Molly, Elizabeth, Edward, Emma, Julet and James.

If this were the case then William would have been born in or before 1777, making him 22 when he enlisted and 43 at his death. Edward would have been 18 at enlistment, 21 when he married Susan Liffin and 23 when he died.

The father of the family, Edward, died in 1812 but the mother, Mary, survived until 1852 and appears in two censuses living with her daughter in Sutton Scotney, to the west of Winchester. On her death certificate her age was recorded as 9920, making her the longest living ancestor in my tree.

This family all seem to have been recorded as Hinxman by the local vicar but each signed their name as Hinksman. All except the parents and their eldest daughter, Jane, could sign their own names. The children must have taught by someone other than the vicar of Twyford to spell their names with a K, rather than X.

However, this connection is still tentative and not without problems, requiring more research. For more on this see the diary entries for 22 Jun 2024 and 23 Jun 2024.21

-

WO 12/2197; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1798-1799; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

See diary entry for 31 Aug 2023 ↩︎

-

Historical Record of the Fourth, or the King’s Own, Regiment of Foot; Richard Cannon; Project Gutenburg ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

WO 12/2198; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1800; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎

-

WO 12/2199; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1801; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎

-

WO 12/2200; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1802; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎

-

Banns for Winchester St. Maurice; 1780-1833; No. 409; Hampshire Archives and Local Studies; Winchester, Hampshire, England; Anglican Parish Registers; Reference: 82001/1/23; Ancestry.com. Hampshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921; database on-line (image) ↩︎

-

Following the Drum: British Women in the Peninsular War; Sheila Simpson; 1981 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Class: HO107; Piece: 758; Book: 22; Civil Parish: Earsham; County: Norfolk; Enumeration District: 10; Folio: 8; Page: 8; Line: 9; GSU roll: 438852 ↩︎

-

WO 12/2201; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1803; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎

-

The Recollections of Rifleman Harris, Benjamin Harris; Project Gutenburg ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

WO 12/2204; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1806 - 1808; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎ ↩︎

-

WO 12/2205; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1809 - 1811; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎

-

WO 12/2205; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1812 - 1814; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎

-

WO 12/2205; 4th Foot 1st Battalion Muster Books and Pay Lists 1820 - 1822; The National Archives of the UK ↩︎

-

Jane Hinksman; 10 Aug 1812; Portsmouth; Hampshire, Portsmouth Burials; 1801-1812; CHU 2/1A/9; Portsmouth History Centre ↩︎

-

Bishop’s Transcripts for the Diocese of Winchester; Marriage entry for George Ponsford and Maria Hinxman, Alverstoke, 6 Jan 1828, Page 215, No 645 ↩︎

-

Beccles House of Correction: Lists of Prisoners (1791-1848); 20 Mar 1824 to 27 Mar 1824, Reference A1122/8/94, No 38, Jane Hinksman ↩︎

-

Registry of Shipping and Seamen: Index of Apprentices; Class BT150, Piece 21, Surnames A-J (1845-1847), Page 490 ↩︎

-

Death entry for Mary Hinksman, Winchester & Hursley, Jan-Mar Qtr 1852, Vol 2c, Page 44, No 110; Digital image obtained 23 Jun 2024 ↩︎

-

Richard Hinxman, maintainer of the Hinxman one-name study has tentatively associated William with two potential candidates: (a) William Hinksman baptised 25 Apr 1774 in West Tytherley, Hampshire, son of Mary Hinchman or (b) William Hinksman baptised 1772 in Romsey, Hampshire, son of James Hinksman and Sarah Withers. ↩︎