Patricio Herrera: A Chilean Sailor's Life in Wales and Yorkshire

Written by Ian Davis. Started 25th January, 2026. This is a work in progress. The substance of the story is complete but there are still some rough edges and missing areas that need to be fleshed out. This document was authored with generative AI assistance for writing, rephrasing, and organising content. All information has been reviewed for accuracy.

Preface

I don’t believe Patricio Herrera was a relative of mine. However, my great-great-grandfather Joseph Hemmings lived in Risca at the same time as Patricio, and there’s a possible connection that led me to research Patricio’s life.

There has long been an oral tradition within our extended family that an ancestor originated from South America or Mexico, and we believe this was Joseph. When he married my great-great-grandmother Bridget Dineen in 1872, his name was recorded as Joseph Ximenes – a name of Spanish origin, with other variants being Jimenez, Himenez, and Himenes. Joseph was recorded in the civil registration version of the marriage entry as Himenes. At some point he anglicised his name as Hemmings, and all records of him and his family thereafter are under the name Hemmings.

Beyond this, though, we have no other evidence for the origin of Joseph Ximenes. We cannot find him on any passenger lists, crew lists, census returns, immigrant records, naturalisation or army records. There’s no trace of him at all in England or Wales before his marriage in 1872. We have no idea when he arrived in Wales, whether it was as a child or an adult, or whether he came alone or with family.

So it’s possible that my ancestor knew Patricio. They would have had a common language (Spanish), common religion (Roman Catholicism), and similar backgrounds, especially if Joseph had worked as a sailor. Joseph didn’t marry until he was thirty-two, which suggests he could have been at sea for several years beforehand. Joseph also worked in the mine at Risca – and was later to die there in 1880.

At the time, the only Roman Catholic church in the area was St. Mary’s on Stow Hill in Newport. Potentially, Patricio and Joseph may have both attended, and it’s possible they may have referred one another to the mining work available in Risca. However, we have to caveat all this with an important timing issue: Patricio left Risca at the end of 1871 to move to Yorkshire, but the first documented evidence of Joseph in the Newport/Risca area is his marriage to Bridget in 1872 at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, where his abode was recorded as Risca and his occupation as coal miner. This implies that Joseph was already resident in Risca at the time and working at the mine there – but after Patricio had departed. So if they did know each other, it must have been during an earlier, undocumented period of Joseph’s time in the area.

Patricio’s story is remarkable in its own right: a documented account of a Chilean sailor who made his life in the Welsh valleys. His preserved letters and journal give us a rare glimpse into the experience of a nineteenth-century immigrant. Even if Joseph Ximenes and Patricio Herrera never knew each other, Patricio’s journey illuminates what Joseph’s might have been like – the adjustment from sea to coal mine, from Spanish to English, from one world to another.

I first learned about Patricio Herrera in a book called Man of the Valleys, The Recollections of a South Wales Miner1, where he was mentioned as a Spanish refugee who was working in Risca in the 1870s.

The information and additional documents in this biography are drawn from the website created and hosted by Roland Herrera, with research by Marian Gill (née Herrera), Patricio’s great-granddaughter. The website is now offline but may be viewed via the Internet Archive.2

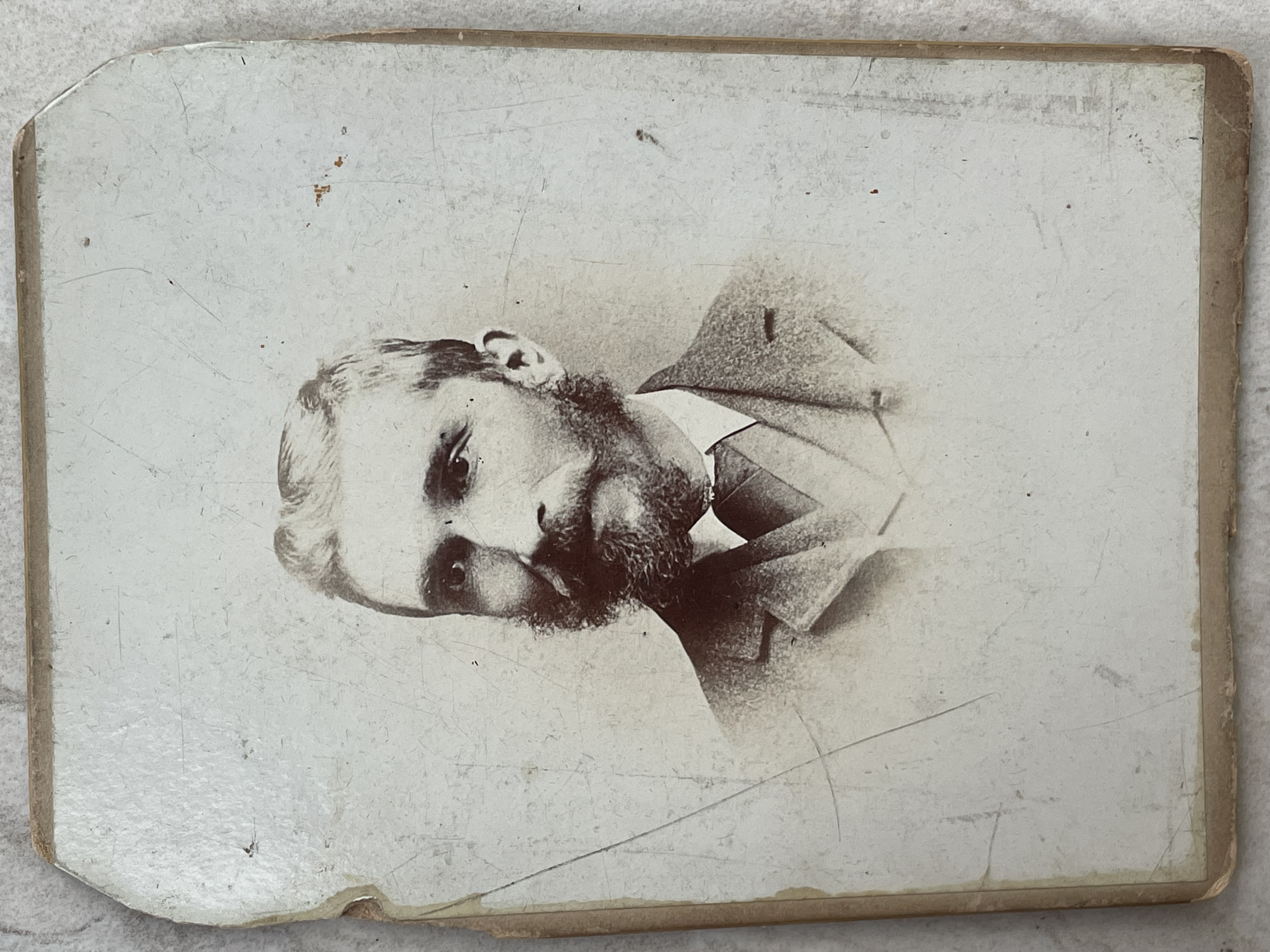

Patricio Herrera

Photograph of Patricio Herrera (undated)

Patricio Herrera was born on 11th July 1849 in Concepción, Chile, though his journal records his birthplace as Coquimbo, a coastal city about 300 miles north of the capital Santiago. These discrepancies in the documentary record aren’t uncommon for nineteenth-century immigrants, and I haven’t found independent verification to confirm which location is accurate. What’s clear is that Patricio came from Chile’s Pacific coast, a region shaped by maritime commerce and mining.

Patricio’s father was Hermenegildo Herrera, born about 1800 in the Concepción area and baptised on 22nd March 1800 in Santa Rosa, Los Andes, Aconcagua, Chile. He was the son of Miguel Herrera and Josefa Lucero. His date of death is unknown, but he died before December 1855. Patricio’s mother was Felipa Canelo Carrillo, born in 1830 in Valparaíso, Chile. She may not have been baptised until 29th January 1848 in San Sebastián, Yumbel, Concepción, Chile – the late baptism suggests either irregular record-keeping or unusual family circumstances. Her father was Manuel Canelo and her mother Manuela Carrillo.

After Hermenegildo’s death, Felipa married William Archibald Bate on 24th December 1855 in Concepción, Chile. William Archibald Bate had been born in 1832 in Margate, England, the son of a commander in the Royal Navy. In the 1851 census he was living in Devon with his mother, now a widow – this would be Mary Bate, whose affectionate letters to Patricio from Dartmouth in 1865 survive among the family papers. How William Bate came to be in Chile by 1855 isn’t recorded, but British merchants, engineers, and naval officers were active along the Chilean coast throughout the nineteenth century, drawn by trade opportunities and the country’s mining industries. William’s elder brother Thomas held a position with the Chilean navy.

Felipa’s later life took some complex turns. In 1867, while still married to William Archibald Bate, she had a child with Francisco Masafierro Coco, a daughter named Blanca Masafierro Canelo – Patricio’s half-sister. William Archibald Bate died on 26th October 1878 in Magallanes, Chile, in the far south of the country. On 18th February 1887, Felipa married Francisco Masafierro Coco at Viña del Mar, Valparaíso, Chile. She died the same day. The circumstances of her death on her wedding day aren’t explained in the records, but the timing suggests she may have been gravely ill and the marriage was arranged to regularise her relationship with Masafierro before her death.

According to Patricio’s journal, on 1st April 1861 the head of his household was William Bate, and he was living at “The Chemist, Main Street, Coquimbo” with his mother.

The Seafaring Years: 1864–1868

In December 1864, when he was fifteen years old, Patricio left Chile aboard the iron schooner West Australian. His journal states he “left my native land December 1864 spent Christmas at sea few days out of the port of Tome Chile.” The West Australian had been built in Hartlepool in 1859 and was owned by Williamsons of Liverpool. The ship had been in Valparaíso on 15th December 1864, so Patricio likely joined her there for the voyage to Liverpool.

The West Australian had earlier in 1864 sailed from London to Wellington under Captain Luke, departing on 22nd March and arriving on 1st July with about eighty passengers and a surgeon superintendent named Dr Thirsfield. The voyage Patricio made was from New Zealand via Napier and Valparaíso to Liverpool, though I don’t know the exact arrival date in England.

Patricio kept a journal during part of this voyage, recording daily life aboard ship from 1st January to 18th January 1865. The entries reveal the routine of a young sailor learning his trade – washing decks during the morning watch, rattling down rigging, making sinnet, and taking his turn at the wheel. On 3rd January they spoke to a ship bound for Montevideo from Valparaíso with wheat, just six days out. On 4th January they caught a small shark measuring four feet long and retrieved a cask covered in barnacles, hoping it might contain spirits but finding only tallow. The weather was often fresh with squalls, and they tacked ship repeatedly. The journal then has pages set out for recording a passage from Talcahuano (a port about 280 miles south of Santiago) to Liverpool, but nothing was written in those pages. The compiler of the website notes that the journey around Cape Horn would have been difficult, leaving little time for writing.

Following his arrival in Liverpool in 1865, Patricio continued at sea. His timeline records Christmas 1865 in Montevideo, South America, aboard the American ship Young Eagle; Christmas 1866 in Dunkirk, France, still on the Young Eagle; and Christmas 1867 in Boston, North America, on a Scottish bark whose name he couldn’t recall when writing the entry years later.

Two letters from Mary Bate in Dartmouth, dated 27th July 1865, survive among family papers. They show the affectionate concern of a step-grandmother for a young man far from home. Mary Bate writes that she had been “very poorly and obliged to go under my doctor’s care,” apologising for the delay in writing. She mentions that Patricio had left Captain Luke, whom she calls “a great favourite of mine,” and asks him to write and tell her what he intends doing. The letters also mention looking out for letters from “your Uncle” which would be kept for Patricio’s return. These fragments suggest a network of family correspondence spanning Chile, England, and wherever Patricio’s ships took him.

Another letter survives from Patricio’s mother Felipa, written from Viña del Mar (a coastal city in the Valparaíso region) on 2nd July 1868. Writing in Spanish, she expresses happiness at receiving his letter and learning “that you are a good young man as I had always wished.” She’s pleased to hear he has a new captain but was sorry he’s no longer with Captain Luke, though she notes the change was a promotion. She asks him to request that his captain “looked after you like a father and taught you how to write some numbers to do accounts,” and offers to host the captain in her house should he ever come to Chile. She asks if Patricio is already a pilot, requests that he write to her in Spanish, and sends her photograph along with one from “Carolina who always thinks of you.” The letter reveals a mother’s continued care for her seafaring son and her hope that he’s acquiring the skills – literacy, numeracy, navigation – that would advance his career.

Arrival in Wales and Marriage: 1868

By Christmas 1868, Patricio’s seafaring life had brought him to Risca in Monmouthshire, Wales. He records that he was “in Risca just arrived from Spain ship Forest King.” The Forest King (registered as number 53346) was a Newport-registered vessel that would eventually be lost in the Bay of Biscay in 1877, an area then used extensively by whaling ships.

Risca in the late 1860s was a rapidly industrialising coal mining town in the Ebbw valley, about five and a half miles west-northwest of Newport. The town had been transformed by coal extraction from the early nineteenth century. Just eight years before Patricio’s arrival, on 1st December 1860, an explosion at the Black Vein Colliery at Risca had killed more than 140 men and boys along with twenty-eight pit ponies, one of many catastrophic mining disasters that marked the development of the South Wales coalfield. The 1870–72 Imperial Gazetteer describes Risca as “a thriving place, dependent chiefly on the collieries, tinplate works, and chemical works of Pontymister and Tydee,” with a population of 2,744 in 1861. It was a town shaped by coal, with terraced housing for miners climbing the valley sides.

It was in this industrial landscape that Patricio met Louisa Thomas, who had been born on 8th January 1851 in Monmouth, about fifteen miles northeast of Newport. Louisa was the youngest of nine children. Her father was John Thomas from Breconshire, and her mother was Jane Philips of Mitchel Troy, Monmouthshire. Louisa’s mother Jane died in 1854, when Louisa was only three years old, and her father John died in 1871. This means Louisa was orphaned at twenty, the same year she and Patricio moved to Yorkshire with their young daughter Caroline. They married on 17th August 1868 at Newport Registry Office. There’s a discrepancy here – Patricio’s journal later records the marriage date as 23rd August. The most likely explanation is that they had a civil ceremony at the registry office on 17th August (the date on the certificate), possibly followed by a religious blessing on 23rd August. Patricio, coming from Chile, was almost certainly Roman Catholic, whereas Louisa, raised in Monmouthshire, was likely Anglican. At the time, marriages between Catholics and Anglicans couldn’t be solemnised in church, requiring a civil ceremony at a registry office. If the couple then sought a religious blessing a few days later, Patricio might have remembered that later ceremony as the “real” wedding date when compiling his timeline years afterwards.

In a letter dated 3rd September 1870, written from Risca and addressed “Dear Father,” Patricio writes to someone who appears to be his stepfather William Bate (though the relationship isn’t entirely certain). He apologises for not writing sooner, saying “circumstances have not permitted.” He acknowledges receiving a letter with news of Bate’s mother’s death – this would be Mary Bate of Dartmouth, whose affectionate letters from 1865 survive. Patricio writes: “I must tell you that the day that I had your letter I was very busy as it was the day after I got married which happened on the 11 of August.” This adds a third date to the confusion – 11th August, rather than either the 17th (certificate) or the 23rd (journal). This may simply be another error of memory, or possibly refers to a betrothal or announcement rather than the actual ceremony. The letter mentions “during that time I have been sailing in coasting vessels as mate but will as my wife has made up our mind to stop until I go home and see if I can better myself there.” He adds that once their little girl can walk, he might get a ship. The child is Caroline Louisa, named after her mother and “Cousin Carolina,” who was nearly a year old at the time of writing (she would turn one on 2nd December).

Another fragmentary letter, apparently written very quickly from “Risca Pier Newport Mon” on 20th April 1871, seems to be addressing someone Patricio knew well enough to share news of his marriage. The letter is difficult to decipher in places, with pieces missing from the edges. Patricio writes about the timing of his previous correspondence: “The day in which I received your letter was the day after I was wedded that was 6 months to the day after I had wrote you, then I put it off day after day not known what to say about being married until at last I have resolve to do it.” This suggests some anxiety about announcing his marriage to this correspondent.

First Years in Wales: Risca and Lower Machen, 1868–1871

The couple’s first child, Caroline Louisa Herrera, was born on 2nd December 1869 at No. 17 Dolphin Street, Newport, at half past four on a Thursday afternoon. Though the birth was in Newport, they were living in Risca at the time, as evidenced by Patricio’s September 1870 letter written from that town.

Sometime between Caroline’s birth and Christmas 1870, the family moved from Newport to Lower Machen, a small village just north of Newport and a few miles east of Risca. Lower Machen was another mining community in the same general area of industrial Monmouthshire. Patricio’s timeline shows he spent Christmas 1869 in Londonderry (presumably in Ireland, though no explanation is given for this journey) and Christmas 1870 in Risca, suggesting the move to Lower Machen occurred during 1870.

By April 1871, according to his letter, they were back in Risca. The 1871 census found the family living in Lower Machen at, or near to, the copper works. Patricio was recorded as a collier, born in Concepción, Chile, but now naturalised. Living with them were Louisa, their daughter Caroline, and Louisa’s father John Thomas, noted as a widower. This was the year John Thomas died, and the fact that he was living with his daughter and son-in-law suggests he may have been in declining health. The census entry also confirms that by 1871 Patricio had already left the sea and was working as a collier.

Yorkshire: Altofts, 1871–1885

In mid-1871, when Caroline was eighteen months old, the family made a significant move north to Altofts in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Patricio’s timeline records Christmas 1871 in “Altofts Yorkshire W Riding,” and this would remain their home for the next fourteen years.

Altofts was a coal mining village about four miles northeast of Wakefield, dominated by the West Riding Colliery owned by Pope and Pearson. The colliery had been established around 1851, when Richard Pope and his partners began working the Stanley Main seam at greater depth than had previously been exploited. The pit was named California after the recent gold rush, with one shaft sunk close to Altofts railway junction and another near the Wheatsheaf Inn in Whitwood township. By 1871, when Patricio arrived, the village had developed distinctive streets: Silkstone Row, North Street, South Street, East Street, and Prospect Place. The longest row of three-storey terraced houses in Europe, Silkstone Row, would stand until its demolition in 1978. The colliery community had established its own Altofts and Normanton Co-operative Society around September 1866, providing workers with essential goods and some social amenities.

The Herreras lived at No. 2 Charles Street, which would be their address for most of their time in Altofts. Here they raised a growing family. John William Herrera was born on 10th July 1872 at half past three in the evening. Herbert H. Herrera followed on 25th August 1874 at 3.30 in the morning. F. Ellen Herrera was born on 2nd May 1877, a Sunday, at 5.50 in the evening.

Patricio’s timeline records one Christmas away from Altofts during this period: Christmas 1876 in “Old Shalston Yorkshire W R” – almost certainly Sharlston, a village and civil parish about four miles east of Wakefield, which includes the settlements of Old Sharlston, Sharlston Common, and New Sharlston. This is very close to Altofts, suggesting the family may have moved temporarily within the same mining district.

By 1880, the family had moved to No. 2 Temple Place, still in Altofts. Florence Gertrude Herrera was born there on 10th October 1880, a Sunday, at 4.08 in the morning. The family would remain in Altofts through Christmas 1884, fourteen years in total. The 1881 census found them at 2 Temple Place, with Patricio noted as a coal miner from Concepción in Chile.

During these Yorkshire years, Patricio was working in the coal industry, though his specific occupation during this period isn’t recorded in the documents I have. The coal mining industry in West Yorkshire was expanding during the 1870s and early 1880s, with deeper shafts being sunk to exploit seams that lay beneath the more easily accessible coal. Working conditions were dangerous – in October 1886, shortly after Patricio had left, a coal dust explosion at Altofts colliery killed several miners when an unskillfully-drilled shot ignited fine dust particles in the dry workings.

Return to Monmouthshire: 1885–1929

At Christmas 1885, after fourteen years in Yorkshire, Patricio and his family returned to the Monmouthshire coalfield. The timeline records Christmas 1885 in “Newtown Crosskeys,” which is Newtown in the Crosskeys area, close to where they had lived in Risca in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

By Christmas 1886, they had settled in Wattsville, a mining community adjacent to Crosskeys and very close to Risca. Their youngest child, Philippa Jane Herrera, was born at No. 4 Wattsville on 5th June 1886, a Saturday, at one o’clock in the morning.

Wattsville sat in the industrial landscape of the eastern valleys of the South Wales coalfield, dominated by the nearby New Risca Colliery, which operated between what is now Wattsville and Crosskeys until 1967. The area had been heavily developed for coal extraction since the early nineteenth century, with associated brickworks, quarries, and metalworks.

According to later census information, by 1891 Patricio had moved to Mynyddyslwyn (which includes the Wattsville area). The 1891 census found the family at 54 Tredegar Street, Mynyddyslwyn, near Risca. Patricio was noted as a coal miner from Chile, a British subject. All their children except Caroline were living with them, along with Louisa’s nephew William Thomas, aged seven, who was lodging with the family.

By 1901, the family had moved to 1 Clarence Terrace in Aberdare, near Merthyr Tydfil. This was a significant move from their usual territory around Risca and Wattsville. Living with them were Caroline Louisa, Herbert, Florence Gertrude, and Philippa Jane. Patricio and Herbert were both recorded as coal hewers. William Thomas was still with them, and Caroline Louisa’s daughter Doris Gwen was noted as Patricio’s granddaughter, aged three.

The 1911 census found Patricio and Louisa at 10 Clarence Terrace in Aberdare. Patricio was working as a coal miner hewer, born in Chile, and his nationality was given as “Chilian.” Living with them was Doris Gwen, now thirteen, but she was recorded as Patricio’s daughter rather than his granddaughter – reflecting the fact that Patricio and Louisa were raising her as their own child. No other family members were present in the household.

At some point after 1911, the couple returned to the Wattsville area. The 1929 death record shows he was living at 78 Islwyn Road, Wattsville. During these final decades, Patricio worked as a colliery fireman – a responsible position involving the maintenance of the ventilation furnaces that were essential for mine safety.

Patricio Herrera died on 9th March 1929 in Wattsville, Monmouthshire, at the age of seventy-nine. Louisa survived him by only eight months, dying on 16th November 1929, also in Wattsville. Together they had spent sixty-four years in Britain, roughly forty-four of them in the mining communities of Monmouthshire and fourteen in the Yorkshire coalfield. Patricio’s life bridged two continents and two industries – the maritime trade of the Pacific coast and the coal mining valleys of industrial Britain.

The Children of Patricio and Louisa

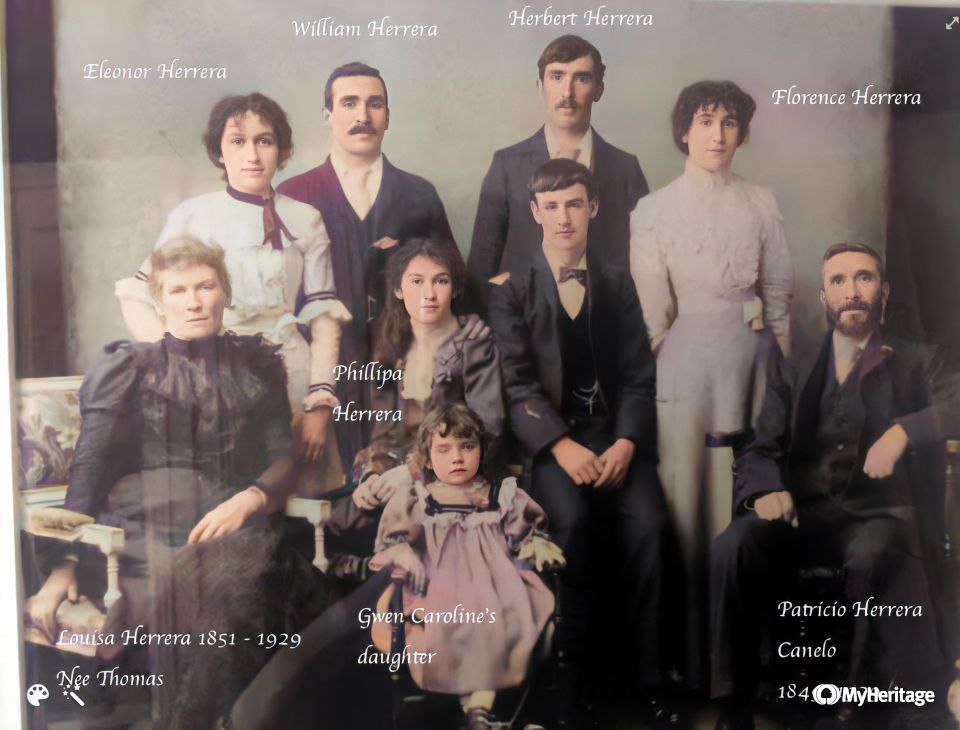

Caroline Louisa Herrera (1869–1943) never married but had two children: Doris Gwen Herrera (1897–1988) and Margery Daisy Herrera (1903–1904). In 1891 Caroline was working as a servant in Llanvedw, Glamorgan. By 1901 she had returned to live with her parents, but in 1911 she was an inmate in the Glamorgan County Lunatic Asylum. She remained institutionalised and died on 7th April 1943 in the Bridgend registration district, Glamorganshire, possibly still in the asylum. Her daughter Doris Gwen was raised by Patricio and Louisa, and in both the 1911 and 1921 censuses she’s recorded as their daughter rather than their granddaughter.

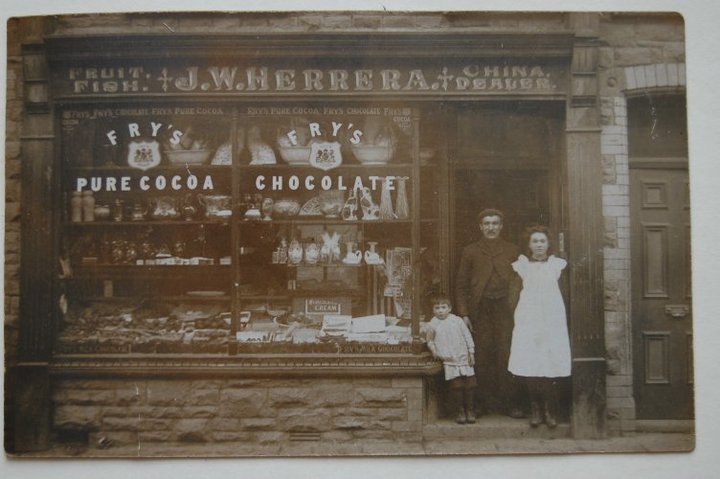

John William Herrera (1872–1956), known as Will, married Mary Ann Lush on 9th March 1896 in Bassaleg, Monmouthshire, in an Anglican church. He was working as a collier at the time, and Mary’s father was a grocer. By 1901 John William had followed his father-in-law’s trade and become a grocer himself. He ran a shop with his wife at 78 Islwyn Road, Wattsville – the same street where Patricio lived. The shop was called J.W. Herrera and they ran it until the 1940s or 1950s. They had five children. John William died on 29th July 1956 in Pontypool, Monmouthshire, and his wife died on 8th March 1963 in the Risca area.

Herbert Herrera (1874–1936) never married. He worked as a collier and lived with his parents in both 1891 and 1901. However, in 1911, like his sister Caroline, he was an inmate in the Glamorgan County Lunatic Asylum. He died on 15th March 1936 at Parc Gwyllt, Coity, Bridgend, Wales, which was presumably the asylum’s address.

Ellen Herrera (1877–1916), known as Nellie, married Thomas Hughes in 1900 and had one daughter with him. She died on 9th December 1916 in Merthyr Tydfil, Glamorganshire.

Florence Gertrude Herrera (1880–1975) married Alfred Hobbs, a collier, in 1901. They had four daughters. She died in 1975 in the Newport registration district, Monmouthshire.

Philippa Jane Herrera (1886–1969), known as Jinnie, married Benjamin Parcell Evans, a butcher, in 1908. They had three children. She died in 1969 in the Pontypridd registration district, Glamorganshire.

Photograph of Patricio Herrera’s family (undated but perhaps 1900 based on the age of the child Doris Gwen)

Photograph of John William Herrera’s shop in Wattsville (undated)

Correspondence

A number of Patricio’s letters and documents have survived. These are transcriptions produced by Marian Gill. She wrote:

These letters were among my Grandmother’s effects (Phillipa Herrera) Patricio’s youngest daughter, there was also a letter from his mother, berating him for marrying an English woman, and telling him to come home. This letter is with my sister Pat.

Patricio wrote a timeline of his life that detailed where he spent each Christmas

I Patricio Herrera left my native land December 1864 spent Christmas at sea few days out of the port of Tome Chile. Bound for Liverpool England in ship West Australia.

Christmas of 1865 I was at Montevideo South America in the American ship Young Eagle

Christmas of 1866 I was in Dunkirk France in the ship Young Eagle

Christmas of 1867 I was in Boston North America in the Bark-I forget the name She was a Scottish vessel

Christmas of 1868 I was in Risca just arrived from Spain ship Forest King

Christmas of 1869 in Londonderry

Christmas of 1870 in Risca

Christmas of 1871 in Altofts Yorkshire W Riding

Christmas of 1872 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1873 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1874 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1875 in Altofts

Christmas of 1876in Old Shalston Yorkshire W R

Christmas of 1877 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1878 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1879 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1880 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1881 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1882 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1883 in Altofts ; Christmas of 1884 in Altofts

Christmas of 1885 in Newtown Crosskeys

Christmas of 1886 in Wattsville

Felipa Canelo Carillo to Patricio Herrera, 2 July 1868

Mister Patricio Herrera

Vista del Mar 2nd July 1868

Dear son,

I received your letter and I am glad to know that you are well. You have no idea how happy I was to read your beautiful letter and to learn that you are a good young man as I had always wished.

It is good to know that you have a nice new boss. Even though I was sorry to hear that you’re not with Captain Luke any more, was happy since it was a promotion. I hope you will behave like a good young man, and please tell that gentleman, your Captain that I would be very grateful if he looked after you like a father and taught you how to write some numbers to do accounts.

If he ever comes to Chile I will be delighted to host him in my house and to thank him personally for helping you.

Let me know if you are already a pilot and please write to me in Spanish and don’t forget to tell me if your boss comes to Chile.

I will send you my photograph and Carolina’s who always thnks of you. I hope you speak many languaes since you have been to so many places, I wish I could visit them too.

With all my heart, from your mother,Felipa Bate

Carolina M[asafierro Coco] to Patricio Herrera, Undated

My dearest Patricio,It was very nice to receive a letter from you and to know that you are in good health. Since we did not hear from you for such a long time we were afraid that you had forgotten about us. I am looking forward to seeing you and when you come back I wil punish you for misbehaving with those naughty gringas. Because of them you have forgotten about me, but not a day goes by without thinking of you and wishing to see you.

I hope you will come one day as a Captain and I will be able to sail with you, because I would love to see the world. Please make every effort to come as soon as possible. I hope you have not forgotten my recommendations to be an honest man, with good judgement, and to choose good friends. I am dreaming of seeing you one day, very smart with gloves and uniform, very elegant.

Goodbye dear Patricio, until I have the pleasure of giving you a big hug in person.

Carolina M

Best wishes from Francesca and Alejandro who are also looking forward to seeing you.

Mary Bate to Patricio Herrera, 27 July 1865

South Town Dartmouth

July 27th 1865

My dear Patricio

I should have written to you before but I have been very poorly and obliged to go under my doctor’s care and am not much better now but would not delay writing as I felt that you would be very disappointed did you not hear from me. My daughter would have written you but she has been in London for the last three weeks, she is quite well and sends her love. I am sorry you should not have left Capt. Luke as he was a great favourite of mine but has you say it cannot be helped. Now be sure you write and let me know what you intend doing. I am anxiously looking out for letters from your Uncle. Should any come for you I will be sure to keep them until you return. I cannot write more now I feel very poorly, be sure you write soon and with kind love.

Believe me dear Patricio

Yours affectionately Mary Bate.

My dear Patricio

I had this letter returned to me to day. I had made a mistake in the number. I am sorry for it as I know you must have been very disappointed. I wrote again yesterday but I hope I have not made the same mistake. I should be glad to hear when you sail. My daughter Mary writes with much love.

Believe me dear Patricio

Yours most affectionately Mary Bate.

Patricio Herrera to William Bate (probable), 3 September 1870

Risca September 3 1870, Dear Father

I now take the pleasure of writing these few lines hoping they will find you in good health, as I am happy to say it leaves me at present.

Dear father I dare say you think me very unkind not to have written before but I must own to you that circumstances have not permitted. I received your most kind letter from which I find you and the family was quite well although I was very sorry to read the painful news of your mother’s death. I did not have a letter from your mother after I left Newport although I received great many from her during the time I was in Newport during which time I had the pleasure of receiving your sisters likeness which I carefully have kept for her sack. I must say that I was very glad to find from your letter that you had joined the Navy. I am very glad to hear it as I hope you are doing much better.

Dear father I must tell you that the day that I had your letter I was very busy as it was the day after I got married which happened on the 11 of August * during that time I have been sailing in coasting vessels as mate but will as my wife has made up our mind to stop until I go home and see if I can better myself there. So soon as our little girl do walk I should get a ship to go. The little girl will be 12 months old the 2 day of December. She is called after her mother and after Cousin Carolina. She is called Caroline Louisa. I have no more to tell you at present but hope that we shall soon meet again.

I remain yours faithfully, Patricio & Louisa Herrera.

Patricio Herrera to unknown recipient, 20 April 1871

Risca Pier Newport Mon

April 20 1871

Dear Sir with much pleasure I write these few lines to you with the ever hopes that they might find you in good health as I am happy to say this leaves me at present and also my wife and daughter. Dear Sir I must tell you for why I have not wrote to you before. The day in which I received your letter was the day after I was wedded that was 6 months to the day after I had wrote you, then I put it off day after day not known what to say about being married until at last I have resolve to do it.

Patricio Herrera to unknown recipient, undated

Dear sir I have much to apologise for but first allow me to say and to hope this will find you all in good health as I am happy to say this leaves me at present, thank you for it. now let me apologise for keeping silent all the time and knowing well where to write to. I surely received your letters and was glad to hear that you are going in the navy and that you had your salary I am also thankful for your good wishes in my health my pen can not describe my fury I now find for the past. Now I feel compelled to write to but I really do not know whether my letter will be welcome or not. I am well aware that I ?frown? my ingratitude and do not deserve acknowledge a thing from you but I pray that you hand? to me the. I promise faithfully to keep up a correspondence with your daughter.

-

Mary Paget, Man of the Valleys, The Recollections of a South Wales Miner, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1985, page 55. ↩︎

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20120207101829/http://www.wps.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/patricio_herrera.htm ↩︎