James Jennings Smith and the Lion Mutiny

Written by Ian Davis. Started 24th September, 2024. This is a work in progress. The substance of the story is complete but there are still some rough edges and missing areas that need to be fleshed out.

James Jennings Smith, chief engineer of the Lion steamship, found himself at the centre of two significant legal cases in 1848. The first case involved his role in leading what was described as a mutiny aboard the Lion, a steam-powered vessel engaged in trade between London and Friesland, Holland. The second followed shortly after, as Smith pursued a claim against his former employer, Captain Henry William Neville, for unpaid wages. These intertwined cases offer insight into the challenging dynamics of maritime labour and the power struggles between shipmasters and crew.

The Lion Steamship

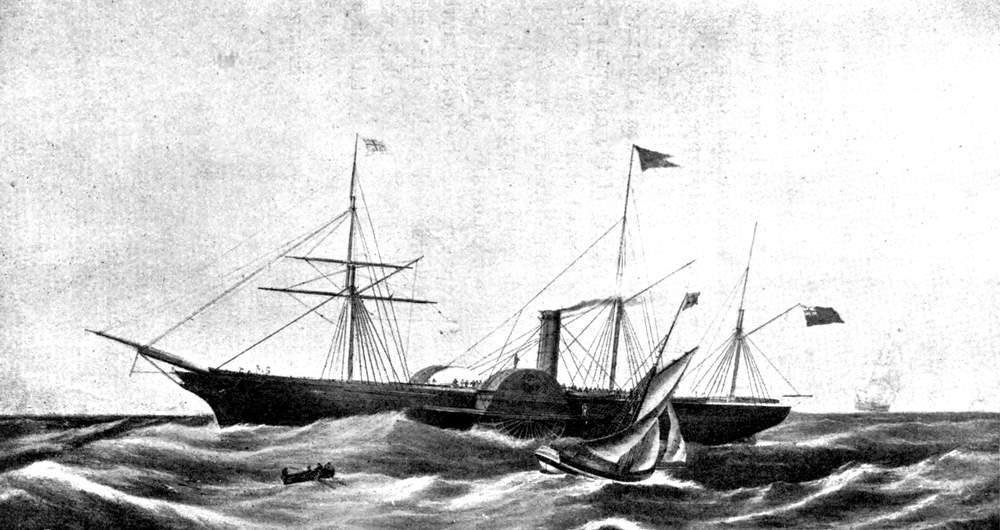

With a tonnage of between 600 and 700 tons, the Lion was a sturdy, well-sized vessel for its trade routes. It was powered by a coal-driven steam engine, which required constant attention from engineers like James Jennings Smith and his team of firemen and coal trimmers. Their work ensured that the ship’s boilers maintained the right pressure to keep the engines running smoothly.

The Lion was not solely reliant on steam power. It was also equipped with three masts, suggesting that it could operate under sail when necessary. This hybrid capability was not uncommon for steamships during the early days of steam navigation. The sails acted as a backup in case of mechanical failure or when coal supplies were running low.

Steamships of this era, including the Lion, had become vital for short-haul trade routes like the ones between London and Holland, and having both steam and sail power offered flexibility in dealing with the sometimes unpredictable conditions of the North Sea.

A three-sailed paddle steamship

Smith had been employed as chief engineer aboard the Lion since early 1848, earning £21 15s per week. The ship made regular weekly voyages to and from London and the Netherlands throughout the year, its destinations varying between Rotterdam, Amsterdam and Harlingen.

For several months, Smith carried out his duties without incident, but a confrontation during the ship’s return voyage from Harlingen in September 1848 led to a major disruption.

The Harlingen Incident

On 13 September 1848, the Lion departed London heading to Harlingen, Friesland, where it was loaded with butter, cheese, flax, oil, and livestock. The ship was bound for London’s markets, and time was of the essence, especially for the perishable goods. Smith, along with the rest of the crew, worked under Captain Henry William Neville to prepare the ship for its return journey.

On the 16th, tensions erupted. Smith attempted to load several baskets of poultry aboard the vessel, intending to sell them in London. While crew members had previously been allowed to bring provisions aboard, Captain Neville refused permission, likely due to the excessive quantity of poultry this time. Witnesses later testified that Smith reacted furiously, reportedly shouting, “Now I’ve got you, you b—-r, I’ll stop the ship!” and immediately ordered the firemen to “rake the fires out.” The steam engines were crucial to the ship’s operation, and by shutting them down, Smith effectively halted the vessel’s departure.

Neville, attempting to calm the situation, urged Smith not to act rashly, telling him, “Don’t make a fool of yourself, and do that which you’ll be sorry for hereafter.” But Smith ignored these warnings, continuing to rile up the rest of the crew, shouting, “Rake the fires out, you b—-rs, and come ashore with me!” In defiance of their captain, many of the crew members, including firemen and coal trimmers, followed Smith ashore, leaving the Lion stranded in Harlingen.

It soon became clear that Smith’s influence over the crew was substantial. Testimonies later revealed that Smith’s loyalty extended beyond simple camaraderie. When some crew members hesitated to join the mutiny, others invoked national pride to pressure them. One witness recalled, “Two or three of the prisoners came on board and asked M’Donald if he had any Scotch blood.” The implication that a predominantly Scottish crew stood together, and that to hesitate would be a betrayal of that solidarity, perhaps played a role in the unified response of the men.

For the next three days, the Lion remained stranded in Harlingen. Captain Neville, along with local authorities and agents, made several attempts to convince Smith and the crew to return to their duties, but Smith resisted. He continued to taunt Neville, calling out from the shore and mocking his inability to move the ship. The crew’s refusal to return to work resulted in significant financial losses, as the perishable goods had to be offloaded and new engineers hired. The ship, now understaffed and unable to sail, faced a costly delay that threatened its cargo and the shipowners’ profits.

Legal Proceedings at Mansion House

On 27 September 1848, James Jennings Smith and the other crew members were tried before the Lord Mayor at Mansion House, charged with “piratical revolt.” Their request for bail was denied, and they were remanded in custody, underscoring the seriousness of the charges, which under the 11th and 12th Acts of William III equated mutiny with piracy—a crime that could carry severe penalties.

They returned to Mansion House on 4 October 1848 for a final examination. This time, the court granted bail, allowing Smith and the others to prepare for their upcoming trial at the Central Criminal Court, commonly known as the Old Bailey.

The Old Bailey Trial

The Old Bailey

Neville recounted that Smith had loudly ridiculed his authority throughout the ordeal, shouting, “Where’s your b—-y Mr. Robinson now? Why don’t you take your ship away?” These taunts were echoed by other crew members, who hurled similar insults at the captain. Despite Neville’s attempts to regain control of the situation, the crew’s loyalty to Smith—potentially bolstered by their shared Scottish identity—meant they refused to return to work.

However, during the trial, a key flaw in the ship’s management emerged: no formal agreements had been made between Captain Neville and the crew, as required by maritime law. Without such contracts, the prosecution’s case was weakened, as the crew could not legally be held accountable for abandoning their posts. As a result, the trial concluded on 1 November 1848 with a verdict of Not Guilty, and Smith and the crew were released after having spent the night in Newgate Prison awaiting the verdict.

The Wages Dispute

After his acquittal, Smith pursued his own legal claim. On 30 November 1848, he brought a case against Captain Neville at the Thames Police Court, seeking £21 15s in unpaid wages for the week ending 16 September. Smith argued that he had been wrongfully dismissed during the dispute in Harlingen and that his actions—extinguishing the fires—were motivated by safety concerns, not defiance.

Captain Neville countered this argument, maintaining that Smith had abandoned the ship voluntarily and encouraged the crew to do the same. Neville also claimed that while it had been common for crew members to bring provisions aboard, the excessive amount of poultry this time was unreasonable and disruptive.

The case took an unexpected turn when two engineers, called by Smith as witnesses, testified that Captain Neville had attempted to reconcile with Smith by offering him money to return to his duties. This testimony contradicted Smith’s claims that he had been forced off the ship, casting doubt on his narrative.

Magistrate Yardley ultimately ruled against Smith. He concluded that Smith had improperly abandoned the Lion and led the crew to follow his example. As a result, Smith was denied his claim for a full week’s wages but was awarded two days’ pay for the time before the incident, along with the costs of bringing the case to court.

Sources

- Shipping and Mecantile Gazette, No 3292, 28 Sep 1848

- Shipping and Mecantile Gazette, No 3346, 30 Nov 1848

- Morning Herald (London), No 20687, 4 Oct 1848

- Morning Herald (London), No 20737, 30 Nov 1848

- Leeds Intelligencer, No 4928, 7 Oct 1848

- Proceedings of the Old Bailey, JAMES JENNINGS SMITH. ALEXANDER REID. JOHN JAMES. DAVID GILLIES. JAMES PAYNE. JOHN KELLY. ROBERT BARCLAY. EDWARD SORRELL. JOHN MCDONALD. Miscellaneous; piracy, 23rd October 1848, No 2400